Founding of MediaArtLab, 2000

— the first institution in Russia that works with media art

Following the worldwide trends, art was actively developing in Russia in the late 90s: there were new technologies, video and sound art, net art, all kinds of experimental forms, referencing both Russian avant-garde artists, such as Malevich and Eisenstein, and Western artists of the 60s, such as Nam June Paik. The artist Alexey Isaev had also been working in these new artistic fields, since he believed that new technologies imply new forms of thinking and it was the duty of an artist to reflect on them. However, at some point, Alexey realized that all the experiments of Russian artists would very soon be forgotten and no one would even consider them artists, unless there was someone who wrote about them and introduced their work to the professional art discourse. It was not that these artists themselves didn’t write about their work or communicate with each other, but still, there was no institution that would purposefully deal with just such art. For that reason, the artist Alexey Isaev and art critic Olga Shishko founded MediaArtLab and started collecting Russian video art, describing and systematizing artworks and promoting artists at the same time. And they managed to achieve a lot in their work.

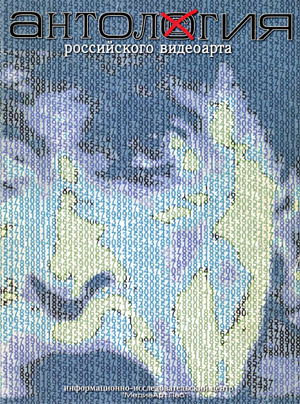

The Anthology of Russian Video Art

— the first ever attempt to compile a collection and write the history of Russian video art

The Anthology was published in 2000 by a group of experts led by Alexey Isaev, which included both artists and film critics. In 2002, these video works were screened as part of the program of the Moscow International Film Festival, which was a very important statement on video art as an integral part of global screen culture. Just imagine: an international A-class festival, a respected event in the world of cinema, with a rich history, famous filmmakers and jury members, premieres, a red carpet... And it showcased a video art program, which, at the time, was by no means distinguished by technical excellence, glamour, or large budgets. Cinema projection operators complained to the festival management that they were provided with damaged films for screenings; the audience consisted mostly of the art community, and nevertheless, for the first time in the world, video art officially entered the program of a large commercial festival. Soon video art works were included in the programs of festivals in Venice and Cannes, and Shirin Neshat’s work won the Golden Lion.

Media Forum of the Moscow International Film Festival

— annual program at the intersection of video art and cinema

Despite the fact that The Anthology of Russian Video Art paved the way for video art to be accepted into the film industry, the idea of an annual art program as part of the MIFF still seemed too bold and a little crazy. Moreover, MediaArtLab invited all the most important people in international arts, artists and theorists who knew that they were celebrities, but no one heard of them in Russia. The question how to attract guests and journalists to these events still remained open. Moreover, the festival had parallel screenings with the participation of well-known actors and directors. The symbolic turning point came, perhaps, at the moment when Peter Greenaway arrived at the Moscow Film Festival not for the main program, but to see the Media Forum, announcing immediately that cinema was dead. He held a screening of his multimedia film The Tulse Luper Suitcases, which turned into a party where Greenaway himself acted as a VJ and which, of course, everyone wanted to attend. Later this collaboration resulted in a huge video installation The Golden Age of the Russian Avant-Garde, which occupied the entire space of the Manege exhibition hall and was created by Greenaway specially for the Russian audience in collaboration with MediaArtLab team. The English filmmaker analyzed the biographies of twelve Russian artists of the early 20th century and told the story of the wreck of their highest hopes as a result their consent to cooperate with the regime.